I spoke about using metaphor a few posts back. This is basically thinking in pictures. Now, you can go beyond just using tropes and breathe visual life into these metaphors with actual pictures and videos salted and peppered throughout your revision.

Just like I try to put a pic at the top of each article that links to the article's content in an interesting and memorable way, so you could illustrate your revision notes with a few choice pics/Photoshop mash-ups/film stills that are odd enough to be highly memorable while still being relevant. (For memory geeks out there, this phenomenon where oddity improves memory is called the 'bizarreness effect'. Read more about in this Google book).

I strongly advise trying it out because you are going have to pack a lot in over the coming months. Even if you conservatively estimate that for each course there are 50 references to remember that's approximately 500 to somehow get into your head. This is the same sort of number that expert memorizers deal with when they remember multiple packs of cards or whatever their memory fetish is. There's a neuroimaging study that shows tricks like these are not due to difference in brains but difference in strategies.

The majority use a visual memory trick called the loci method, which dates back to the Greek poet Simonides of Ceos. You may have heard of it. Simonides was at a banquet when the roof collapsed. Many of the people were crushed beyond recognition and he was able to recall who was there by imagining the positions of people seated at their tables. I suggest having a brief read of this short review from TICS for the scientific account.

Whatever's going on beneath the brain's bonnet, one thing I am confident of is that this method works. As the author of the paper says, "Mnemonic methods are effective in generating associations between otherwise ‘meaningless’ or unrelated information, such as dates and names" (which precisely characterises a reference). There are stats somewhere that I can't find right now but which show big memories gains from using this method over the slog-it-out-write-'em-down-ten-times approach.

I did this for both references and essay arguments. Take the paper I mentioned a sec ago, for which the references is Ericsson (2003). Translate this into something memorable as you revise. How about it's 20:03 and Eric has forgotten (the paper is about memory) to pick his son up from school? Draw a little sketch of a panicked parent, the forlorn child and the clock on the wall.

For extended arguments you have built, you can do the same. I can still remember lots of the little stories I made up to mirror the arguments. Not only is this helpful to your learning but it injects some fun into the learning process (which probably makes your learning more effective).

One thing I like doing and which gives you a nice entry point to the loci method is to find a photo or make a sketch and then add details of the experiment in pithy form to the pic. I have uploaded a few for you all on my Flickr account, in the Mind Bites set (click here for the slideshow). If you fancy doing something like this yourself, you can use free Photoshop alternatives like the newly launched Photoshop Express, good old GIMP or easy-as-pie Flauntr.

For extended arguments you have built, you can do the same. I can still remember lots of the little stories I made up to mirror the arguments. Not only is this helpful to your learning but it injects some fun into the learning process (which probably makes your learning more effective).

One thing I like doing and which gives you a nice entry point to the loci method is to find a photo or make a sketch and then add details of the experiment in pithy form to the pic. I have uploaded a few for you all on my Flickr account, in the Mind Bites set (click here for the slideshow). If you fancy doing something like this yourself, you can use free Photoshop alternatives like the newly launched Photoshop Express, good old GIMP or easy-as-pie Flauntr.

You might scoff at this method as adding extra work to your already busy desk. Well, yes, but that information is more suited to the natural channels through which memories flow. So, it's a weird case of adding more information to do less work.

Other things might work for you, but this worked for me. Think in pictures and you'll think more clearly, remember better and enjoy the work more.

Here are a few I made earlier...

Split brain - the axe is attacking the posterior corpus callosum, which is the major information highway between the hemispheres.

Split brain - the axe is attacking the posterior corpus callosum, which is the major information highway between the hemispheres. Prosopagnosia, obviously. Less obviously, The F & G in the eyes stand for Fusiform Gyrus which is thought to be the associated dysfunctional area

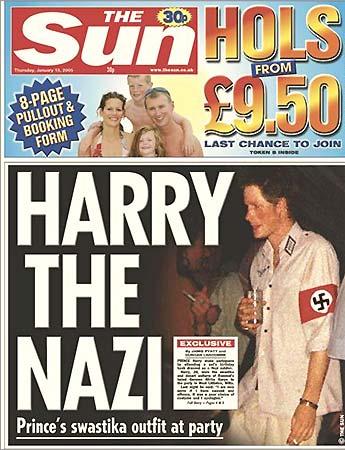

Prosopagnosia, obviously. Less obviously, The F & G in the eyes stand for Fusiform Gyrus which is thought to be the associated dysfunctional area A symbol worn on the arm with connotations of hatred and being on the political 'right'. Useful for remembering misoplegia, which is hatred of a limb (e.g., an arm) due to right hemisphere damage.

A symbol worn on the arm with connotations of hatred and being on the political 'right'. Useful for remembering misoplegia, which is hatred of a limb (e.g., an arm) due to right hemisphere damage. Good one for neuropsychiatry: everything comes down to the brain (if its attended to) even distant cultural things, like The Simpsons.

Good one for neuropsychiatry: everything comes down to the brain (if its attended to) even distant cultural things, like The Simpsons. The male cast of Friends for male sexual strategies. Joey, the high-genetic quality/high-masculinity/low-investing male who is massively polygamous ("How you doin' ?") vs Chandler the lower genetic quality/low masculinity/high investment male who is relatively monogamous. Ross appears to operate both strategies, which is a useful way of capturing context-dependent sexual strategies.

The male cast of Friends for male sexual strategies. Joey, the high-genetic quality/high-masculinity/low-investing male who is massively polygamous ("How you doin' ?") vs Chandler the lower genetic quality/low masculinity/high investment male who is relatively monogamous. Ross appears to operate both strategies, which is a useful way of capturing context-dependent sexual strategies.Another good one for the male polygamous strategy would be this Lynx ad which taps into this desire for many partners and portrays it in absurdly epic proportions.

This one is for optimal female sexual strategy. Here females are particularly attracted to high developmentally stable (masculine) males (cues to high genetic quality) around ovulation (hence the egg) meaning they can get all best resource investment off Mr Lovey and the best genetic investment off Mr Hottie.

This one is for optimal female sexual strategy. Here females are particularly attracted to high developmentally stable (masculine) males (cues to high genetic quality) around ovulation (hence the egg) meaning they can get all best resource investment off Mr Lovey and the best genetic investment off Mr Hottie. Looking time/violation of expectancy paradigms can be remembered by the surprised baby.

Looking time/violation of expectancy paradigms can be remembered by the surprised baby.Two clips for alien hand syndrome. The first from Red Dwarf

and the second from the combined genius of Sellers and Kubrick in Dr Strangelove

Topically, John Prescott, has today admitted to suffering from bulimia nervosa (purging type). His case is useful for neuropsychiatry because it shows this is not just a disorder that affects Western females, as the popular impression goes. Secondly, it smashes another popular myth: that eating disorders are merely the product of the media portraying skinny girls. I can't really see Prescott leafing through Vogue. That is not to say psychological factors are irrelevant; he says one of the causes of the disorder was stress - a known risk factor. There are lots of neurobiological correlates that are emerging (see Kaye, 2008, for a good review) but one Prescott might be useful for remembering is that the disorder has been associated with a 'crap' right temporal lobe (e.g. Levine et al., 2003). This is because Prescott is left-wing and considers the right 'crap'.

Topically, John Prescott, has today admitted to suffering from bulimia nervosa (purging type). His case is useful for neuropsychiatry because it shows this is not just a disorder that affects Western females, as the popular impression goes. Secondly, it smashes another popular myth: that eating disorders are merely the product of the media portraying skinny girls. I can't really see Prescott leafing through Vogue. That is not to say psychological factors are irrelevant; he says one of the causes of the disorder was stress - a known risk factor. There are lots of neurobiological correlates that are emerging (see Kaye, 2008, for a good review) but one Prescott might be useful for remembering is that the disorder has been associated with a 'crap' right temporal lobe (e.g. Levine et al., 2003). This is because Prescott is left-wing and considers the right 'crap'.And finally, it's not a photo but it's barking up the same tree:

"In this country, you gotta make the money first. Then when you get the money, you get the power. Then when you get the power, then you get the women."

- Tony Montana in Scarface.

The idea nested here is one the evolutionary psychology literature on risk-taking, aggression and homicide knocks about, namely, that access to females is the end goal, in the strict Darwinian sense. Power and wealth are means by which to get there and if you don't have these things it's worth taking risks for them.

Anyway, you get the idea. Go and be creative with your revision: it will sink in better...